The Dunn Cemetery–Indiana University (Part Three)

NOTE:

The following article was originally published in the Fall 2023 edition of the Indiana University Alumni Magazine. Aerlex Law Group founder and President Stephen Hofer is an Indiana alumnus and thought our Aerlex audience might find it of interest, even though it’s definitely “off-topic,” at least as far as business aviation is concerned. This is the third in a four-part series. Stick with it through all four parts – we think you will ultimately be at least a little entertained and charmed by what you’ll learn about the Indiana University campus, a pioneer graveyard, Revolutionary War patriots and the founder of our firm.

By Deborah Galyan

Although a number of burial petitions come to IU each year, most are dismissed outright for not meeting the Brewster descent requirement. Occasionally, petitioners have a good grasp of the records needed for proof and have already obtained most of them. These are referred to Aerlex Law Group President Stephen Hofer in his capacity as the genealogical curator and trustee of the Dunn Family Cemetery. “In those cases, I will try and help,” Hofer says. “If I can do some research and find something that will help them break through the barrier, I’ll do it.”

The tough part of the job is turning people down when they fall short of proving their lineage. “It can be heartbreaking,” he says.

Hofer doesn’t envy the person who served in the curatorial role before him and had the difficult task of turning away Indiana music legend Hoagy Carmichael, LLB’26, DM Hon’72. A devoted IU alum, Carmichael is said to have been deeply disappointed. The composer of “Stardust,” “Georgia on My Mind” and a trove of Tin Pan Alley hits, Carmichael was laid to rest in Bloomington’s Rose Hill Cemetery in 1981. You can still visit him on campus—forever seated at his piano— immortalized in a sculpture by Michael McAuley, BS’78, MS’82, located just steps east of Showalter Fountain.

Like all cemeteries, the Dunn Cemetery is a repository of information, serving as a conduit to the people and events that shaped our present-day community.

“Sometimes people say that death is what gives meaning to life—and the places where people reflect on death tell us a lot about the changing realities of the living,” explains Eric Sandweiss, a professor and scholar of public history and memory at IU Bloomington.

Cemeteries, he explains, are places where “two important historical resources intersect.”

The first is text, in the form of genealogical information and in expressions of faith. The second is the shaped landscape of the site, which, he points out, “is itself a kind of text.”

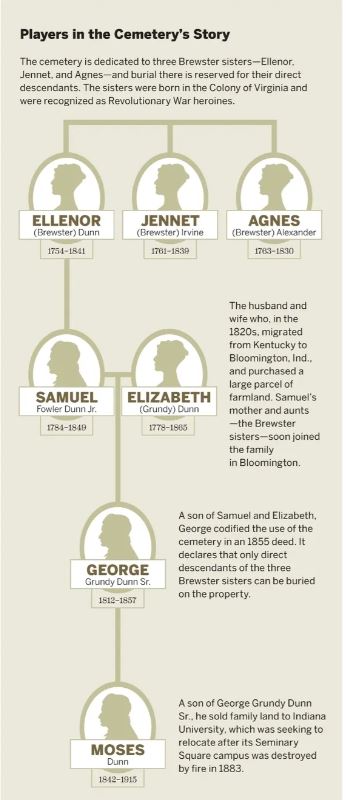

Revolutionary Sister Act

It doesn’t take long to find the Brewster sisters’ monument in the diminutive cemetery. A three-sided pillar stands tall in the northwest corner of the yard, carved with their names, in order of youngest to oldest.

- Agnes Brewster Alexander (1763–1830)

- Jennet Brewster Irvine (1761–1839)

- Ellenor Brewster Dunn (1754–1841)

All three were born in the Colony of Virginia, near Augusta, in the Shenandoah Valley. Eventually, they settled in Bloomington, Ind., to be near each other and their children, who had begun moving to the new Indiana Territory in the late 1700s. All three died in Bloomington.

And then, a surprise. A plaque installed on the marker declares the sisters “Revolutionary War Patriots,” as decreed by the Daughters of the American Revolution.

It’s a discovery that presumably explains why George Grundy Dunn Sr. dedicated the cemetery to his grandmother and great-aunts. It also raises questions: How did the Brewster sisters become war heroes at a time when women were largely confined to domestic life? What acts of patriotism did they perform, considering they would have been ages 12, 14, and 21 when the first shots were fired at Lexington and Concord?

Hofer is somewhat circumspect about declaring the Brewster war stories unequivocal truth, given the lack of primary sources—no firsthand accounts such as letters or diaries written by the sisters have been found to date. But there are compelling secondary sources, including “The Revolutionary Service of the Brewster Sisters,” a document written around 1912 by four of the Brewster grandchildren. Their account aligns with much that is known about women’s roles during the Revolutionary War, as illustrated in these excerpts:

The family of James Brewster, of Augusta County, Virginia, gave strong and unfaltering support to the cause of American Independence. It was a family chiefly of daughters, but they gave to their country the result of their supreme effort as loyal women. … They knit, spun, wove, sewed and cooked to provide for the needs of the soldiers who could be reached by them. …

[T]hey did not wait for the regular sheep shearing time to renew their supply, but would catch the sheep (of which they had a great number), clip the fleece, and turn it into yarn as fast as possible and put it in the loom. As soon as a web was long enough to make a suit it was cut from the loom, made up, and sent to the front. … It is a fact well known to their descendants that these women … in times of peril, melted up their household utensils of pewter and moulded bullets from it.

Although standards of proof are generally more rigorous today, Hofer says, the grandchildren’s account held sway with the Daughters of the American Revolution. In 1913, the Brewster sisters were officially recognized as Revolutionary War Ancestors.

NOTE: This is the Third of Four Parts.